Revisiting Pitcher Arsenal Analysis

Defining a different paradigm for pitcher analysis with real-world application

This will largely build on concepts discussed in my previous piece about arsenal construction. I recommend reading/re-reading it to fully understand what will be shared here.

Introduction

Hitting is all about timing. Taking the inverse of that, we would see that the primary goal of a pitcher is to disrupt timing. Of course pitchers have the ability within their physical limitations to influence the shapes of their pitches, but those may have less of an impact on pitcher effectiveness than initially thought. Release characteristics matter far more than many “Stuff” models can even begin to quantify. Why? Because they struggle to fully account for how a batter perceives a pitch and subsequently tries to get on-time for it.

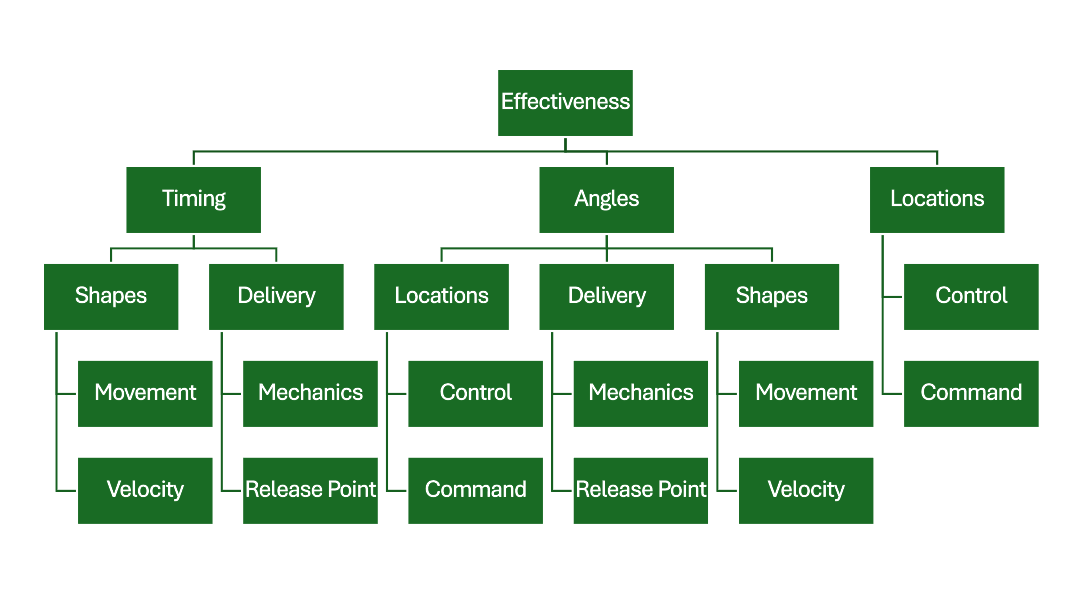

This is what led me to identify that pitch shapes and release characteristics work together to create the two of the three main areas of my focus. The first of which is the angle the pitcher creates when delivering the ball. VAA and HAA are nothing new, and even HRA and VRA are relatively common in most spheres. I believe these would be one of the optimal components for pitcher development and evaluation to focus on. The shape is less important to the batter than the angle it creates both out of the hand and in relation to the zone.

The second area of my focus in relation to shapes and release characteristics is timing. Pitchers can affect timing a number of ways in regards to their shapes and delivery. This includes things from velocity to occlusion and even having a hitch in their delivery.

The third area of my focus is somewhat separate from the first two: location. Location is comprised of control and command. While they are two different things, I’m including them in the same area because they are things a pitcher can heavily influence, and they are dependent on the purpose of a pitch. There isn’t a single “good” way to control or command all pitches across a given arsenal. The framework here is highly individualized, so there are only optimal rates for different pitches in an arsenal depending on the purpose of a given pitch and its context.

Lastly, I’ve made a couple adjustments to some labels to reflect the changes in my initial theory. I’ve changed the “FP” (fast pitch) label to “PP” for Primary Pitch. This refers to the most utilized in-zone pitch a pitcher throws regardless of velocity or shape.

The “SiP” designation simply refers to Secondary In-Zone Pitch now without consideration for movement or velocity. Similarly, “SoP” no longer takes into consideration movement or velocity. Both are primarily focused on usage, control, and command.

I have created a visual to help conceptualize the relationships between angles, timing, and control and command.

Analysis in this framework

Before we take a look at a couple of examples, there are three questions to ask about a pitcher when analyzing them under these new parameters:

What difficult angles can a pitcher create?

How does a pitcher disrupt timing?

Can a pitcher locate their pitches in optimal spots?

And these are the three categorizations of pitches with different designations:

aPP or gPP: an arm-side or glove-side primary pitch utilized in-zone

aSiP or gSiP: an arm-side or glove-side moving pitch utilized in-zone less than the PP

aSoP or gSoP: an arm-side or glove-side moving pitch utilized out of the zone

Yu Darvish

A good pitcher to test any pitching theory or model on is Yu Darvish because he throws so many distinct shapes from what’s really four different pitches.

Primary Pitch (Slider and Sweeper)

Darvish uses a gPP that he has advanced feel for to attack the zone at an above average 60.4%. He almost triple it’s breaking movement at the expense of 3-4mph when needed, so overall hitters need to be prepared to see it in the 82-86mph range. His lower-than-average release height coupled with solid extension and a longer-than-average horizontal release creates difficult angles even when his locations are sub-optimal. Both gPP variations play well in-zone primarily due to the horizontal angles he creates and how they pair with his aSiP shapes.

Part of what makes Darvish so unique is that his gPP shape operates between his aSiP and gSoP shapes both in terms of movement and velocity. Most pitches have a PP shape that requires SiP shapes to blend and connect to their SoP shapes. PPs with less total movement are generally easier to command, and those tend to be the higher velocity shapes. Darvish is an outlier because his gPP variations have quite a bit of movement. This speaks to his advanced feel for control and command of that pitch.

Secondary In-Zone Pitch (Two-Seam, Four-Seam, and Cutter)

Darvish deploys a trio of aSiP shapes ranging from 91-94mph at an above average rate of 57.8%. The aSiP variation with the most vertical movement plays best at the top of the zone and above because of the uncomfortable vertical angle it creates coming from a relatively low release height. Darvish has comfortably plus feel for his more runny aSiP shape and uses it primarily to keep hitters from trying to time up his more vertical aSiP. His cutting (but on paper neutral) aSiP variation blends well with his gPP shapes - especially the tighter one. This combination also does well to disrupt timing because of the three velocity bands.

Secondary Out-of-Zone Pitches (Curveball, Knuckle Curve, and Splitter)

We’ll begin with his gSoP shape and its variations. Ranging from 73-78mph, Darvish lands it in-zone at a modest 45.2%. This is much lower than his gPP and aSiP shapes, but that’s understandable because it’s not a pitch he uses to get strikes. SoP shapes are primarily used to get hitters to chase and Darvish is no exception here. There really isn’t much of a significant or functional difference between the two variations of his gSoP aside from the velocity, but they pair well with his gPP (especially the lower velocity variation) to generate chases. So despite their average and somewhat redundant characteristics in relation to his arsenal, they still serve a purpose.

Darvish’s aSoP is quite interesting because it’s his only pitch that doesn’t work off of his gPP variations. It pairs best with the more vertical aSiP shape and somewhat with the running variation. Its primary function is to keep hitters from sitting on the more vertical aSiP and is most effective when located below the zone. This makes sense considering its 43.8% in-zone rate.

Garrett Crochet

Crochet serves as a more practical pitcher to analyze in this framework because he has a more standard arsenal.

Primary Pitch (4-Seam Fastball)

Crochet’s primary in-zone weapon is an aPP with pretty standard movement and a respectable 59.3% in-zone rate. It stands out for it’s plus-plus velocity and near elite extension to create a challenging angle for hitters. Crochet leverages most of his 6’6 frame into creating extension and a horizontal release point which further add to his ability to disrupt timing. Hitters are not used to seeing a LHP with that kind of delivery and velocity. The aPP is a relatively platoon-neutral weapon that helps him leverage count control against RHB, but the emergence of his gSiP as a viable in-zone weapon has propelled him to becoming one of the best pitchers in the game today.

Secondary In-Zone Pitch (Cutter)

This gSiP has decent velocity and vertical separation from his aPP, and shapes with that kind of velocity and tight break tend to play platoon neutral. Being able to land it in-zone over 50% of the time is what has allowed him to effectively navigate lineups multiple times even when they are loaded with RHB. This shape also blends well with his gSoP which further allows for better sequencing as a starter versus when he used to be a limited to a relief role. Pitchers like earlier versions of Crochet who try to blend a PP with a SoP tend to struggle with navigating a lineup multiple times because hitters can more easily anticipate which pitch they will see in a given count.

Secondary Out-of-Zone Pitches (Sweeper and Changeup)

His gSoP is his primary chase pitch as he lands it in-zone 41.3% of the time. It has optimal velocity separation from his gSiP, and has a unique amount of break considering its above average velocity on that sort of shape. His ability to consistently locate it down and glove side allows him to sneak it under the bats of RHB while LHB simply have almost no chance of making contact, let alone putting it in play.

Crochet does have an aSoP, but it is rarely thrown so it’s not something most hitters need to worry about. However, it does blend surprisingly well with his aPP. So when he does sprinkle it in, it is rarely a pitch hitters can do damage on.

Practical Applications of this Framework

A simplified language applicable to all pitchers regardless of the shapes they do or don’t throw allows for a more consistent, uniform type of analysis. It also allows pitchers to be evaluated for what they are with respect to their individuality. Everyone can throw what they want in different ways to achieve the same common purpose. It also allows us to look at the whole pitcher; how they go about disrupting timing and creating difficult angles without favoring different archetypes or guys who pop on “Stuff” models. It’s clearly more complex to analyze pitchers and evaluate performance in this paradigm, but it’s more more holistic and comprehensive so it will yield more thorough and thoughtful results.

Common language is also beneficial in coaching and development because it allows for players to work towards a common goal to build an arsenal that fits the pitcher rather than chasing shapes or doing something that doesn’t make sense for their body. If every pitcher had a 95mph fastball with very little run and 20 inches if IVB, hitters would get more comfortable with those pitches over time and they would be less effective. It’s important to preserve individuality in pitching out of respect for the uniqueness of all pitchers as well as the practical, in-game applications that uniqueness can lead to. Common language can clarify and simplify concepts before they lead to misunderstanding and inconsistencies in messaging.

This common language also inherently values control and command - two things a large faction of modern pitching development and analysis has gotten away from. As stated before, a more holistic view is more complicated and messy, but it is more thorough and thoughtful than simply trying to put labels and numbers on things. That’s not to say numbers and metrics aren’t useful in some capacity, but there’s so much nuance that gets lost when we disregard the context.